A note from Alex

-

Dear readers,

-

-

Last October I stopped posting because I was no longer able to find time to manage this blog. A new semester of my online studies at the University of Manchester had started. I had my family and two jobs to take care of at the same time. So I said goodbye to the blog. I didn’t know whether I would ever return. I was pretty sure the blog would soon wane and die without me.

-

-

Now I have received two comments on my ancient postings from two nice people from different countries in the last few days. I logged on and was amazed to discover that the blog had been living a life of its own without me. The number of views per day has been on the rise and I have got new subscribers. Having googled my blog’s name and getting a number of hits (for the first time), I understand that google must be the reason. Which gives me inspiration to return here someday and carry on my noble mission of educating humankind (but mostly myself) about languages and cultures :-). With my still heavy study- and workload, however, it might not happen until summer. See you then my friends!

-

-

All the best,

-

Alex

Another language gone: Cochin Creole Portuguese

Someone may argue it is not a language at all. The opinion that Creole languages are nothing but dialects, or bastardized versions, of ‘real’ languages has been widespread, although it is no longer as common as it was before. One thing is for sure – there is a culture behind each Creole language which is very distinct from that of their parent language.

When Europeans colonized faraway lands in the 15th and the following centuries, the local populations had to interact with the colonizers and developed simplified versions of English, French, Portuguese and other colonial languages, which became known as pidgins. Later, these pidgins were ‘normalized’ or ‘nativized’, i.e. learned by the children of pidgin speakers, passed from generation to generation and eventually became Creoles. Often, Creoles appeared where groups of people were uprooted from their native places and had to move, for example as slaves, to a land where their native language was not spoken at all.

The vocabularies of Creoles are full of cognates from their parent languages, however the grammars usually differ greatly from those of the parent languages and are modeled on the grammars of local dialects spoken before the Europeans came. Unlike pidgin grammars, the grammar of a Creole can be quite complex. For example, Jamaican Creole features largely English words superimposed on West African grammar. (I find this a very interesting fact as it seems to prove to me that grammatical knowledge is implanted in the mind on a deeper level while vocabulary knowledge is more superficial and can relatively easily be replaced).

I found this paper by David B. Frank on the characteristics, origin and current state of Creole languages very interesting. The title is We Don’t Speak a Real Language: Creoles as Misunderstood and Endangered Languages and you can read it here.

Here is a quotation: “As linguists debate why or whether or how creoles constitute a unique class of language, we should not lose sight of the fact that we are talking about the mother tongues of real people with their own unique culture, identity, history, and forms of communication.”

As it happens, many Creole languages are facing extinction, and two weeks ago another Creole ceased to exist. Here is a tribute to Cochin Creole Portuguese. Another language is gone, and the world is continuing to lose its linguistic diversity.

Are you a good language learner?

J. Rubin listed the following characteristics of a ‘good language learner’:

1. The good language learner is a willing and accurate guesser.

2. The good language learner has a strong drive to communicate, or to learn from communication.

3. The good language learner is often not inhibited.

4. In addition to focusing on communication, the good language learner is

prepared to attend on form.

5. The good language learner practises.

6. The good language learner monitors his own speech and the speech of others.

7. The good language learner attends to meaning.

Rubin J. (1975) What the good language learner can teach us. TESOL Quarterly 9(1): 41-51.

Good points but maybe a trifle too technical. I would add being open-minded, culturally-sensitive and ready to tune into other ways of thinking.

A new language is more than just a new system of symbols or vehicle for communication. It’s a new culture and a new mode of thinking.

Any more additions to the list?

Huun Huur Tu

Some cultures are known for their art more than anything else. These cultures would have little chance of being noticed by more than a handful of academic people, were it not for some unique art they possess and for some talented people carrying the art to the outside world. The first example that springs to mind is Tuva (aka Tyva) and the Tuvan (Tyvan) throat singing.

Tuva is a Russian autonomous republic in East Siberia on the Mongolian border. Tuvan is a Northeastern (or Siberian) Turkic language, spoken by 200,000 people in Tuva plus some in Mongolia and China. It is closely related to the Khakas and Altai languages. The Mongolian and Russian influences on it have been quite strong too. In the past, Tuvans used to write with Mongolian script. The Latin-based alphabet for Tuvan was devised in 1930 by a Buddhist monk, Mongush Lopsang-Chinmit. A few books and newspapers, including primers intended to teach adults to read, were printed using this writing system. But then Lopsang-Chinmit was executed in Stalinist purges on December 31, 1941. A new Cyrillic-based alphabet was introduced by decree in 1943 and is still in use.

It was not the writing system of Tuvan that particularly interested me, however, but the phonetic system, because I thought there must be something about the language itself that gave birth to the unique art of throat singing – a style of singing in which two or more pitches sound simultaneously over a fundamental, very low pitch, sound. This musical art is related to the overtone singing/chanting done in Tibet and Mongolia, especially by Buddhist monks, but the Tuvans have taken it further, to the point where some Tuvans can even produce three audible tones simultaneously.

At the root of throat singing is human mimicry of nature’s sounds. Tuvan tradition is that of herdsmen living in the steppe. The open landscape of Tuva allows for the sounds to carry a great distance. Often, singers will travel far into the countryside looking for the right river, or will go up to the steppes of the mountainside to create the proper environment for throat singing.

I went to the concert of the most internationally known Tuvan music group called Huun Huur Tu here in Perm in July this year. The Opera House, where they were performing, was packed despite the 35 degree heat outside and no air conditioning inside. These musicians have a lot of devoted fans across the world and they are almost always on tour.

A little skeptical at first, I was glad to discover that it was more than just a circus trick. It was real art. The musicians combine throat singing with other types of singing, and their voices and instruments blend to produce a mesmerizing effect. I was soon carried away to another reality. During one particularly sound-rich song, I closed my eyes and experienced a sort of trance. I saw huge black birds darting overhead, animals rushing wildly across the steppe, I heard a waterfall rumbling in the distance… A grandiose shamanic ritual was taking place by the riverside, the shaman and his people performing a weird dance. I saw it all vividly like in a movie. That’s one healthy way to get high!

Anyway, it’s better to see once, so here is a bit of their performance at the 2006 Philadelphia Folk Festival. It is not the same song that entranced me at the concert but still a great one. (Nor does it demonstrate the whole gamut of possibilities of throat singing, but search Youtube to hear more).

What about the phonetics of the language then? Is the language itself responsible for the appearance of this genre of singing? Here is what I have found out.

Vowels in Tuvan exist in three varieties: short, long and short with low pitch. Contrastive low pitch may occur on short vowels, and when it does, it causes them to increase in duration by at least one-half. When using low pitch, Tuvan speakers employ a pitch that is at the very low end of their modal voice pitch. For some speakers, it is even lower and they use what is phonetically known as ‘creaky voice’. When a vowel in a monosyllabic word has low pitch, speakers apply low pitch only to the first half of that vowel. This is followed by a noticeable pitch rise in the second half of the vowel. The acoustic impression is similar to that of a rising tone in Mandarin, although the Tuvan pitch begins much lower. Despite the similarity, Tuvan is considered a pitch accent language with contrastive low pitch instead of a tonal language. These low pitch vowels were previously referred to in the literature as either kargyraa or pharyngealized vowels.

So it seems that the language itself trains Tuvans to combine various pitch levels and makes them capable throat singers. But it does require special talent to take this trick to the level of art, and that is why I admire Huun Huur Tu. Between the songs, they also tell their audiences about Tuvans, their language and traditions. They have done a lot to make their small nation with its wonderful culture known to the world.

P.S. Curiously, while googling for throat singing I discovered that another ethnic group famous for such skill is Inuits of Canada. And their performers are usually women!

Spelling reform or a parody of Mark Twain?

I don’t know if someone is pulling my leg, I am going crazy, someone else is going crazy, or I am just being boring and conservative. Somebody tell me which it is. I’m talking about this piece of news:

Now the part about the French crying out against the Anglicization of Europe makes perfect sense: it’s an eternal rivalry, and the fact that English has come ahead in the battle for global and European domination cannot possibly please the French. The argument that French is ‘more precise’ I believe is ridiculous, but they had to say something to belittle English anyway.

The part that makes no sense to me at all is the suggested ‘language reform’ (at the end of the article in italics). I was so shocked that I actually set up an account on Express.co.uk in order to comment on the article. Here is what I wrote:

I wonder if this is anybody’s poor joke or plagiarism of Mark Twain? Or both? Here’s Mark Twain’s proposal – could it be that someone didn’t notice he had his tongue in his cheek?

”A plan for the improvement of spelling in the English language

By Mark Twain

For example, in Year 1 that useless letter “c” would be dropped to be replased either by “k” or “s”, and likewise “x” would no longer be part of the alphabet. The only kase in which “c” would be retained would be the “ch” formation, which will be dealt with later. Year 2 might reform “w” spelling, so that “which” and “one” would take the same konsonant, wile Year 3 might well abolish “y” replasing it with “i” and iear 4 might fiks the “g/j” anomali wonse and for all.

Generally, then, the improvement would kontinue iear bai iear with iear 5 doing awai with useless double konsonants, and iears 6-12 or so modifaiing vowlz and the rimeiniing voist and unvoist konsonants. Bai iear 15 or sou, it wud fainali bi posibl tu meik ius ov thi ridandant letez “c”, “y” and “x”— bai now jast a memori in the maindz ov ould doderez —tu riplais “ch”, “sh”, and “th” rispektivili.

Fainali, xen, aafte sam 20 iers ov orxogrefkl riform, wi wud hev a lojikl, kohirnt speling in ius xrewawt xe Ingliy-spiking werld.”

I still hope the italicized part of the article was a joke. If not, I think the time has come for me and others to campaign for the preservation of the English language. I’ve been lamenting the loss of minority languages but it’s English that is in danger.

Folks in the UK familiar with Daily Express, is it prone to joking like that?

How to become superhuman

Had Nicholas Ostler’s Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World delivered to me from Amazon this morning. I really like the opening line: “If language is what makes us human, it is languages that make us superhuman”. Now I can justify calling this blog ‘languages blog’ rather than ‘language blog’. It’s a blog for superhuman readers! 🙂

Beautiful Tibetan

I have always been fascinated by mountains. My father was a mountaineer in his youth, so a love of mountains must be somewhere in my genes. Unfortunately, I have loved them vicariously most of my life. The Ural Mountains, next to which I live, are old and weathered and really look like hills. Last time I stood on top of something that could qualify as a mountain was 23 year ago. I was 15 and I had climbed some minor Caucasian peak with my father and a group of tourists.

On the way up, my foot had slipped and I went tumbling down the slope. Not a very steep slope, fortunately, but before I realized what was going on I was lying with my head next to a large boulder and my legs pointing toward the sky. I continued the ascent with my knees trembling. When we reached the summit, however, a panoramic view of the Great Caucasian Range unfolded before me, and the trembling was gone; suddenly I felt ecstatic and awed by the beauty of nature. It almost felt like I was drunk (of course at that age I couldn’t compare). I wanted to laugh and sing. I remember the feeling very well, and the Range is still standing like a photographic image in front of my eyes. I haven’t been to real mountains since.

I think people who live their entire lives surrounded by mountains are a sublime race. I really believe there is something special about them. The beauty and grandeur of mountains is in their blood. Their eyes are directed toward the sky.

Tibetan peoples are like that. Generations and generations of people living in Tibet and the Himalayas have owned the beauty.

Just listen to these Tibetan songs and feel it.

http://www.gakyi.com/tibetansongs/

Tibetan is a language, and Tibetan are languages. There are 25 mutually unintelligible Tibetan languages belonging to the Sino-Tibetan language family. The ‘main’ one is Standard Tibetan. The 25 languages are further subdivided into about 220 dialects. The situation with languages and dialects is complicated by politics. In China, for political reasons, the dialects of central Tibet, Khams and Amdo are considered dialects of a single Tibetan language, while Dzongkha (official language of Bhutan), Sikkimese, Sherpa and Ladakhi are considered separate languages, despite the fact that Dzongkha and Sherpa are closer to Lhasa Tibetan than Khams or Amdo are.

Sadly, the destinies of the language are enmeshed in politics in more ways than just the issue of dialects. In an extensive report entitled China’s Attempts to Wipe Out the Language and Culture of Tibet published on the official site of Central Tibetan government, various organizations and individuals comment on the marginalization of Tibetan. Here are some quotes:

[Despite the fact that Tibetans constitute 96% of Tibet’s total population], “in the organs of the Tibet Autonomous Regional Government and in the varying levels of schools, Tibetan language is gradually being replaced by Chinese. In civil service examinations, there are no Tibetan language tests at all. Government documents are almost always unavailable in Tibetan. In any meeting, big or small, the leaders make their speeches only in Chinese. Therefore, in the social lives of Tibetans, Tibetan language is increasingly being reduced to a valueless status.”

“The areas where Tibetan language can be used are shrinking [by the day]”.

“Generally in the Tibet Autonomous Region, while taking university and college examinations, Tibetan language is given either only 50% weightage or sometimes no weightage at all.”

“That the Tibetan language is not treated with dignity, or for that matter is not utilised, is the harmful effect of the wind called “assimilation” that is blowing. The sharp pain caused by this wind is still being felt [in Tibet].”

“Tsering Dhondup Dherong, a Tibetan intellectual and Communist Party member, has cited three principal reasons for this in his book Bdag Gyi Re-smon. The first, he said, is the Chinese government’s chauvinistic policy, which accelerates the process of Sinicisation; the second is the notion of Tibetan being a worthless language in today’s society; and the third, the inferiority complex suffered by Tibetans, which hampers their initiatives to maintain and protect their own language.”

Of all the above facts, it is the inferiority complex thing that is most alarming to me. I am afraid that if the people themselves have been made to feel inferior speaking their native language, there is little chance that the language might ever rise to a higher status, and its journey toward extinction has already begun.

Project Hebrew

It is an amazing fact that the word ‘excited’ has no Russian equivalent. It seems to be such a common feeling that it’s unbelievable how Russian manages without it. Translators translate it into Russian as either ‘glad’ or ‘aroused’ or something similar to ‘pleasantly agitated’ – which sounds awkward even in Russian. So I can’t say ‘I’m excited!’ in my native language and I’m saying it in English. I’m excited because tomorrow I am going to my first class of a new language. In recent days, I have toyed with the idea of studying several different languages and I shared my feelings about Finnish in an earlier post. However, I have since sobered up (figuratively, of course) and realized that there is little chance I will summon enough motivation to study the language without a tutor. With my hectic schedule I do need someone to report to at least once a week, otherwise I’ll always find an excuse not to study. And I do need someone to practice speaking with.

So walking past the synagogue the other day, I decided to drop in and ran straight into a bearded guy who happened to be a teacher of Hebrew, so I immediately arranged private classes with him beginning this Friday. Now I’m not going to write a long essay on why I chose Hebrew but there seems to be a nice mix of practical and sentimental reasons: I’m half-Jewish, I’ve got family in Israel and, even though they can all speak Russian, I have found myself in situations in Israel where being able to speak Hebrew would have made things more convenient and would have made me feel less like a fool. And the fact that it’s an ancient culture and a beautiful county which I love add to the sentimental feeling.

Hebrew, or Ivr’it, as it is called both in Hebrew and in Russian, is a Semitic language and as such a member of the Afro-Asiatic language family. It is the most famous example of a dead language having been resurrected and being now alive and well.

According to some Jewish traditions, Hebrew was the language of creation and it was the language spoken before things got messed up at the Tower of Babel.

Israeli guides claim that the Hebrew alphabet was the first writing system with letters corresponding to sounds (instead of hieroglyphs, syllable writing, etc), however sources suggest that it developed along with other scripts used in the region during the late second and first millennia BC.

Eventually, Hebrew was displaced as the everyday spoken language of most Jews, and its chief successor in the Middle East was the closely related Aramaic language. It is being debated whether it happened during the Hellenistic period (in the 4th century BC) or at the end of the Roman period (about 200 AD).

For centuries afterwards it remained a language of prayer, studies and religious texts, the language of the Torah and the Talmud.

Then it was revived in its modern version. Hebrew’s revival was initiated in the late 19th century by the efforts of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, who immigrated to Palestine in 1881. The language was reconstructed as a spoken language, retaining its Semitic vocabulary and written appearance but taking on European phonology. It also borrowed a number of idioms and literal translations from Yiddish, which was the first language of many European Jews (Ashkenazi) settling in Palestine.

So tomorrow 9 a.m. is my first class. Anybody who knows Hebrew or has attempted to study it before, I would love to hear from you. What are your impressions from learning the language? What is the fun part and what are the stumbling blocks?

Language education in Europe and Russia: Teach more or teach better?

In my previous post I suggested that knowing one foreign language was enough if you knew it well. A mankind of polyglots would be fantastic, but if everyone succeeded in immersing him/herself into at least one foreign culture, it would already make this world a better place.

If you think about Europe, however, the demands are higher. With the borders open and with 27 nations sharing the same political and economic space while trying to preserve their linguistic and cultural identities, I believe knowing more than one foreign language must be a requirement for everyone from primary school onwards. Because of the closeness and the ease of communication between the countries, Europeans can hugely benefit from learning several languages of their neighbors and, through the languages, learning their neighbors’ cultures.

So what is the situation like today? I have glanced through some facts about language education in Europe, and it is not the same across the Union.

In nearly all European countries, according to the 2008 report, “Key data on teaching languages at school in Europe,” students are expected to begin foreign language instruction in primary school, which is a great thing. Students in Belgium and Spain are often provided such instruction at the pre-primary level. In Luxembourg, Norway, Italy and Malta the first foreign language starts at age six.

Malta is a veritable nation of polyglots. Beginning from primary school the children learn several languages. Watch this report from France 24:

http://www.france24.com/en/20090127-malta-nation-polyglots-?quicktabs_1=0

In Luxembourg, French and German are taught from the primary level, and almost 100% of the adult population are trilingual (the third being their native Luxembourgish). Of course, many of them know English as well. Here is more info about Luxembourg:

http://www.unavarra.es/tel2l/eng/luxembourg.htm

In Belgium’s Flemish community at least two foreign languages are taught in secondary school.

On the other hand, Ireland remains the only country where foreign language education is not compulsory. The Irish and English languages are taught but they are both official languages of the country.

In the UK, students have recently been allowed to opt out of studying foreign languages as early as at the age of 14. They have eagerly grasped the opportunity. They obviously believe that everyone in the rest of the world speaks English anyway. Employers say this will damage British students on the international jobs market. More about it here:

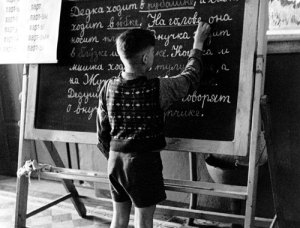

And how are things in Russia, which is geographically part of Europe but is really in its own category? One foreign language is compulsory here from second grade of primary school, and some elite schools offer two or more foreign languages. But thinking about Russia makes one think that quality matters at least as much as, or even more than numbers. I studied English in the USSR from age 11 to age 17 and I could hardly speak any of it when I was leaving school. I could write some sentences and read them, I could translate the texts written in Rusglish from the appalling textbooks we were using with the help of the mini-dictionary provided at the end of the same book, I knew a bit of grammar theory by heart and I always had ‘A’s (‘5’s in our system). Today, things have changed little apart from the fact that kids study English from age 8 and still can’t speak it by age 17. True, in this generation a lot more students actually end up speaking English by the end of their school life, but that is solely due to traveling, the internet and the self-education, and more often than not it happens despite school. Most teachers of English, who work for meager salaries from Kaliningrad to Vladivostok, are elderly women who can’t speak the language well enough themselves (and some of them can hardly speak it at all – believe me, I’ve checked).

What is the conclusion? It’s very simple: There should be a balance between quality and quantity. Since the quality of teaching foreign languages appears to be generally higher in Europe, it’s increasing the quantity of languages taught in schools that tops the agenda there. For Russia it is definitely increasing the quality.

It’s not my goal to be a polyglot. A sports commentator doesn’t have to be a good footballer, car racer, weight-lifter, tennis player and ski jumper, all at the same time, in order to understand the sports and give thoughtful commentary. However, dabbling in a few of the sports will make one less of a theorist and add to one’s credibility. Likewise, I can’t ever hope to be fluent in many languages. I won’t have time to learn them and then constantly practice them to keep them alive. Not meaning to offend anybody, I also believe that learning languages simply for the sake of learning languages is pure self-indulgence. It’s enjoyable, it’s addictive, but unless you actually do something with your knowledge to help mankind, you’re just engaged in a non-stop self-pleasing exercise. It’s fine if you are a linguist studying the languages to analyze the ways they work and make global conclusions. It’s fine if you are a permanent traveler and use your skills interacting with people across the globe. Other than that, I don’t think the numbers matter. Knowing one foreign language well is sometimes more worthy of respect than knowing a dozen languages poorly, in my very humble opinion.

As for me, I’m a bit of a linguist and a bit of a traveler, and in this blog I am trying to be a sort of ‘linguistic commentator’. So I thought it would be great to learn a couple of tongues different from those I had known from birth or had studied before (i.e. Russian, English, French, Spanish and a bit of Italian).

So the other day I decided to study Finnish. Why? Lingustically, because it’s from another language family and, consequently, is unlike all the other languages I know. When I speak Spanish I sometimes get confused and insert French or Italian words. With Finnish, words as basic as ‘yes’ (‘kyllä’) and ‘no’ (‘ei’) are so different that there’s no risk of confusing them. Also, it would be intriguing to see how agglutination works where enormous words are created by joining morphemes together. It would be interesting to study a language with a complex system of inflection of nouns, adjectives, pronouns, numerals and verbs.

To learn a language I also have to like the culture. For some reason I have only positive associations with Finnish culture.

It makes me think of The Snow Queen by Andersen, one of my favorite childhood books, where the Lapp woman and the Finn woman helped Gerda in her quest of Kai.

It makes me think about polar nights, Aurora Borealis, forests, lakes, reindeer, Santa Claus…

I’ve always supported the Finnish ice-hockey team (of course unless they played against Russians), I don’t really know why. Maybe because I want them to match the Swedish team’s record. They always seem to have been a little behind. Maybe I just like their colors.

I prefer Finnish butter. It’s the best you can buy here. Finnish tiles are good. Finnish copying paper is good. Both my son and I have Nokia phones, and they are good.

The Finns’ proverbial liking of vodka should have struck a chord with me as a representative of the vodka nation, however the only two ways I use vodka is to disinfect the injection spot when my wife shoots some prescribed stuff into my buttocks and to please my father-in-law when he comes over for a visit. I don’t drink it.

I traveled to Finland as a foetus. My mother was pregnant with me when her trade union (the organization responsible for distributing tours in the USSR) granted her and my father a much desired tour to a capitalist country. It was not terribly easy to get a tour even to a socialist country in 1971. But Finland had friendly relationships with the Soviet Union, so my parents were allowed to go. Of course, they were first grilled in the local Communist Party office about the political situation in the world, the advantages of the Soviet way of living, etc. They were not allowed to wander away from the group while in Finland or mix with locals. One member of the group was a KGB agent, as it always happened at that time, and my father says it was pretty easy to figure out who it was. Anyway, they enjoyed the visit and were even able to take a few snapshots of half-naked models on posters in window shops, something you couldn’t see in the Soviet Union. So I have something Finnish in my blood because my mother breathed Finnish air and ate Finnish food even as some of my vitally important organs were formed.

After I thus justified my choice of the language to immerse myself into, I needed to find someone to help me learn how to speak it. That’s where the snag was. In the city of Perm, with its one million population, located in the Urals, where the pro-Uralic language originated, with the Komi and Komi-Permyak languages (relatives of Finnish) spoken in nearby regions, there doesn’t seem to be a single Finnish speaker, let alone teacher. I’ve phoned all language centers, asked friends, searched on the internet. No use.

I know it’s possible to learn a language all by yourself if you have plenty of motivation. Maybe you can even find someone to communicate with via skype. But for me, that takes away all the fun of learning languages. I need to have a living person next to me with whom I can speak the language.

Now I’ve got the dilemma: should I go out of my way and try to learn Finnish without a teacher? Or should I settle for a language available in Perm, such as Czech, Portuguese, Turkish, Hebrew or Arabic, all of which are wonderful and intriguing each in its own way? There are quite a few of them taught here – you can even learn spoken Sanskrit but not Finnish!

Something to think about in the next few days…